Over the past seventeen years, I have continually honed my skills in counterstrain to the point where my confidence in treating musculoskeletal dysfunctions is no longer an issue. However, I am reminded each week that despite symptoms of muscular pain and what appear to be orthopedic origins of pain, not everyone responds to neuro-muscular treatment. So what are the other possibilities? True structural defects such as a torn rotator cuff, an intervertebral disc herniation, a fracture or perhaps a stenotic condition in the spine are capable of creating and sustaining dysfunction. Likewise, the neuromuscular dysfunction that we treat with counterstrain is capable of a long-term self-sustaining cycle due to the internal argument between protective reflexes and postural reflexes. So if neither structural defects nor musculoskeletal dysfunctions are to blame, what’s the underlying cause?

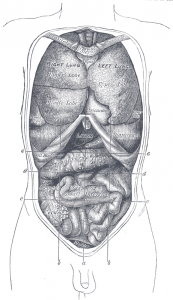

The most integral component of the body is its connective tissue. Another name for connective tissue is fascia and fascia permeates everything. It is part of skeletal muscle, tendons, ligaments, blood vessels and nerves. In addition, it provides anchoring ligaments for organs, compartments for the various abdominal cavities and support structures for holding one organ to another or the retention, of something as large as the colon, to the peritoneum. So the question is, can fascia present a problem? Well most practitioners in the field of bodywork, whether PT’s, OT’s, LMP’s or Trainers, would agree that yes, it can and frequently does present problems. But what exactly is “The problem”?

The most integral component of the body is its connective tissue. Another name for connective tissue is fascia and fascia permeates everything. It is part of skeletal muscle, tendons, ligaments, blood vessels and nerves. In addition, it provides anchoring ligaments for organs, compartments for the various abdominal cavities and support structures for holding one organ to another or the retention, of something as large as the colon, to the peritoneum. So the question is, can fascia present a problem? Well most practitioners in the field of bodywork, whether PT’s, OT’s, LMP’s or Trainers, would agree that yes, it can and frequently does present problems. But what exactly is “The problem”?

If the source of these problems is not a muscle, but a fascial structure, how is the fascial structure involved? If it is tight, why is it tight? If it is stuck, how is it stuck? These are valid questions, ones that I struggled with for many years and that ultimately convinced me that I needed to explore additional ways of affecting the body with manual therapy. I was not going to simply follow the commonly held belief and the mindset that direct manipulation or force applied to the body would result in the release of a myofascial adhesion. Quite simply this was in direct conflict with what I have learned and practiced over the past 10 years.

Counterstain differs from 95% of the manual techniques currently employed by remaining a purely indirect technique. Fascia is in fact contractile. We know this now thanks to some very recent connective tissue research done in Europe over the last 10 years. What Robert Schleip found will forever change the field of manual therapy.

Fascia and connective tissue in general has been largely ignored by the research community because it was thought to be an inert tissue. However, it is not an inert tissue. It has a rich vascular supply and a dense neural innervation. Plus, it has the ability to contract or shrink uniformly. How is this possible?

Well fascia has myofibroblasts embedded within its cellular matrix. Attached at the end of these smooth actin filaments is an elaborate collagen lattice-like apparatus that enables the uniform contraction of the tissue. Contractile elements of the body have both the capacity and the tendency to become dysfunctional. It is now reported in the literature that passive myofascial tension can elevate the tone of skeletal muscle. This is separate from true neuromuscular dysfunction. Neuromuscular dysfunction is a maladaptive protective reflex that originates in the peripheral nervous system due to a communication failure between the gamma system and the muscle spindle. The fascial issue appears to be a totally separate issue. Here is where things get more interesting.

The fascial structures in the trunk, and especially those of the viscera (organ) in the abdominal cavities and chest cavities have an enormous impact on the skeletal muscle of the trunk. Again, having the capability to contract means the ability to apply force. Quite simply the restrictions imposed upon the trunk by the various visceral dysfunctions have very similar effects upon the muscles and joints of the trunk as would your typical musculoskeletal dysfunc-tion. Quite often the symptoms are so similar as to be totally confused with true muscular or joint dysfunction. So how does counterstrain for these visceral/fascial dysfunctions work?

Well it follows pretty much the same general rules of the technique that have existed since Jones first described them 60 years ago. We still shorten the dysfunctional structure, we are just doing so with a much different intent than that of the muscle and joint treatments. We are shortening fascial structures and so the treatment positions may not appear to be doing anything specific without knowledge of the visceral fascial structures in the body. Once you have an understanding of the main fascial structures and the orientation of key visceral anchors, both to the skeletal system and to visceral structures the whole counterstrain approach to visceral treatment appears completely logical and appropriate.

Prior to gaining an understanding of fascial anchors and the anatomy of the abdominal cavities and the organs that inhabit them, even discussing treatment of this region often sounds a bit fringe. I was certainly skeptical when I first learned of this approach, but that quickly faded when I attended the first counterstrain class for the treatment of visceral dysfunction back in November of 2008. As I have now used these techniques for more than 8 years I can honestly say that my entire practice of counterstrain has gone through a complete overhaul. I get more done in a shorter amount of time that I ever thought possible. I am able to deal with issues that stumped me before and I am enjoying an even greater degree of success with my most difficult clients.

If you are interested in receiving treatment, please call the office and schedule an evaluation.

©2009 – Counterstrain Portland®.